THE SIERRA LEONE CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT BILL 2025: OBSERVATIONS AND CAUTIOUS ANALYSIS

Sierra Leone’s 2025 Constitutional Amendment Bill in a Broader African Perspective: Reform, Order, and the Quiet Redesigning of our Democracy----- The Republic Journal (13/100)—Truth, Representation, and the Future of Our Democracy. -by Aminata Diamond

Constitutional reform in Africa has never been about text alone. It has always been about temperament. Every amendment proposal reveals not only what a state wishes to change, but what it fears to preserve. The Constitution of Sierra Leone (Amendment) Bill, 2025, belongs squarely within this continental tradition. It is not yet law, but it is already a statement of constitutional intention. And intention, in constitutional history, often matters more than enactment.

Across Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and South Africa, African constitutions have evolved toward professionalism, proceduralizing, and institutional management. Electoral bodies are redesigned. Political parties are regulated. Judicial timelines are compressed. Representation is recalibrated. Gender inclusion is codified. These reforms are modern, fashionable, and technically persuasive. Sierra Leone’s 2025 Amendment Bill faithfully follows this African reform script.

But constitutional history teaches a difficult lesson: democracy does not decline only through regression. It also declines through refinement.

The first pillar of the 2025 Amendment Bill is electoral governance. Like Ghana, Kenya, and Nigeria, Sierra Leone now proposes committee-based nomination processes for electoral leadership. This mirrors Africa’s search for legitimacy through procedure. Yet the executive gravitational pull remains structurally present. Committees broaden participation, but they do not dissolve influence. Kenya’s repeated electoral crises demonstrate that selection panels do not end political contestation. They merely relocate it. Sierra Leone’s Bill, therefore, does not escape Africa’s unresolved dilemma. It inherits it.

The second pillar is political party regulation. The Bill empowers the deregistration of parties that fail to win elections in two successive cycles. This reflects a growing African appetite for administrative tidiness in political life. But democracy is not a market where only successful products deserve survival. Ghana, Nigeria, and South Africa have resisted turning political failure into constitutional extinction. Sierra Leone’s Bill risks converting pluralism into performance. When the state begins to decide which political voices deserve continued existence, democracy becomes curated rather than contested.

The third pillar is representation. The Bill moves Sierra Leone closer to party-centered proportional representation. South Africa provides the continental model. It has delivered inclusion, but at the cost of weakening constituency intimacy. Representatives are accountable to party leadership more than to communities. Kenya faces similar tensions in its party-list structures. Ghana and Nigeria remain more constituency-rooted. Sierra Leone’s Bill, therefore, marks a philosophical choice. Party architecture is being elevated over personal representation.

The Fourth pillar is gender inclusion. The Bill’s thirty percent quota aligns with continental corrective trends. Rwanda, South Africa, and Kenya demonstrate their value. Yet Africa also shows that quotas without power restructuring often yield only symbolic inclusion. Sierra Leone’s Bill proclaims equity, but leaves enforcement uncertain. Representation without authority remains a promise that can be postponed indefinitely.

The Fifth pillar is judicial compression. The Bill drastically shortens timelines for presidential election petitions. Across Africa, courts already carry the burden of electoral legitimacy. Kenya’s judiciary has endured both praise and political hostility for election rulings. Ghana’s courts have faced similar pressures. Sierra Leone’s Bill now moves in the same direction. Speed may preserve administrative stability, but it risks sacrificing deliberative credibility. A constitution should protect confidence, not merely close files.

When these elements are read together, the 2025 Amendment Bill reveals its deeper philosophy. It does not seek to silence democracy. It seeks to manage it. It does not abolish participation. It reorganizes it. It does not suppress pluralism. It disciplines it. It does not weaken institutions. It refines them.

And herein lies the danger.

Africa’s constitutional lesson is not that reform is harmful. It is that reform can become a substitute for trust. When states redesign democracy for efficiency, predictability, and quietness, they often forget that democracy is meant to be inconvenient, noisy, and uncertain.

South Africa shows that proportional representation can coexist with a strong civic culture. Ghana shows that executive influence can coexist with public trust. Kenya shows that legal process cannot replace political legitimacy. Nigeria shows that institutional complexity does not automatically cure democratic anxiety. Sierra Leone’s 2025 Amendment Bill now stands among these examples, not above them.

The Bill does not betray Sierra Leone’s Constitution. But it proposes to reinterpret it. It shifts the constitutional soul from participation toward procedure, from citizenship toward management, from politics toward administration.

The question, therefore, is not whether Sierra Leone has copied some bigger African democracies. It has. The question is whether Sierra Leone has learned from some of Africa's painful democratic trajectories.

Africa’s democracies did not struggle because they lacked reform. They struggled because reform often arrived without humility, without trust, and without deep civic anchoring.

Sierra Leone’s 2025 Amendment Bill is intelligent. It is professional. It is well drafted. And that is precisely why it must be examined with precision rather than applause.

Because the most dangerous constitutional changes are not those written in anger. They are those written in confidence.

Democracy does not weaken when it is attacked. It weakens when it is reorganized without remembering why it was created.

The Constitution of Sierra Leone (Amendment) Bill, 2025, therefore represents a constitutional moment, not a constitutional conclusion. Whether it strengthens democracy or quietly domesticates it will depend not on the Bill alone, but on the civic courage of those who must debate it, amend it, and ultimately live under it.

History has never forgiven constitutions that forgot their people while perfecting their procedures.

@followers @highlight

#therepublicwillrise #democracy #JudicialIndependence #powertothepeople #usembassysierraleone #eusierraleone #ECOWAS #ECOWASCourt #AfricanUnion #justice #commonwealthcountries

—————————————————

FURTHER OBSERVATIONS AND ANALYSIS!

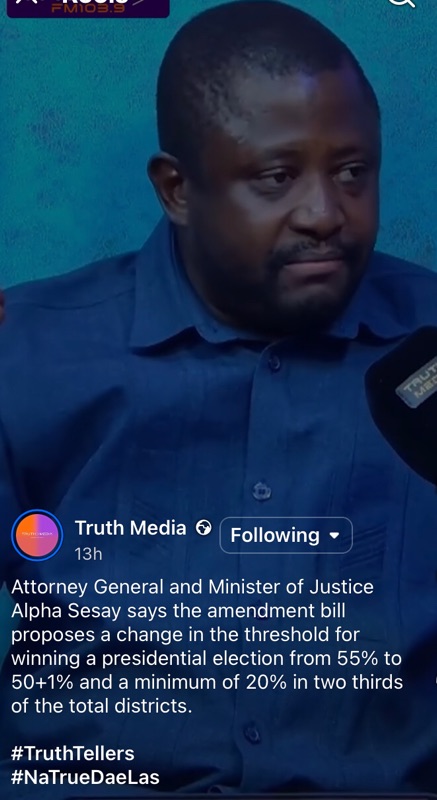

TRUTH TV INTERVIEW- A G SESAY:

https://www.facebook.com/share/v/1Am1Nk8ZfB/?mibextid=wwXIfr

https://youtu.be/kTFHJfErVhs?si=2pS6k3J1017XVJqn

—————————————

———

From Blogger iPhone client

Comments